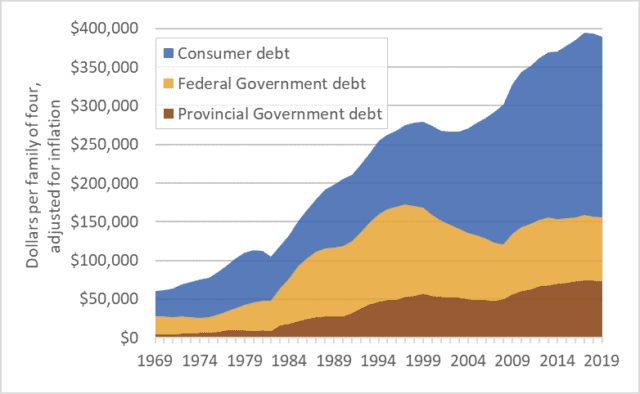

Canada has a debt problem. Total consumer and government debt is now $3.7 trillion, with 60 percent being consumer debt: mortgages, home-equity loans, credit lines, car loans, credit card balances, etc. Provincial government debt is about $0.7 trillion and federal government debt is $0.8 trillion. Corporate and financial-system debts would add trillions more, but we’ll leave those amounts aside.

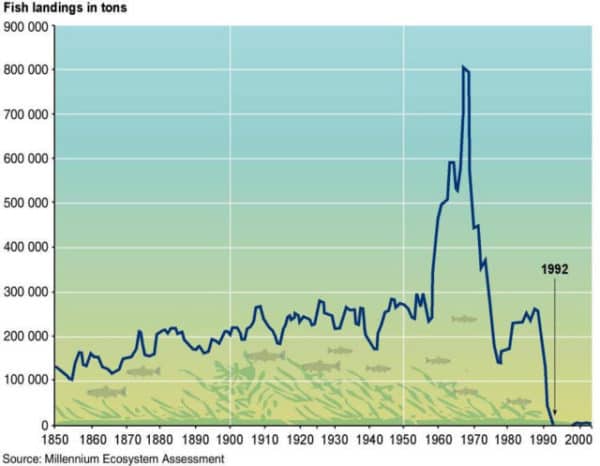

Those are big numbers—too big to make sense of. It is easier to understand debt if we look at it on a per-household basis. The graph above shows debt levels for a hypothetical family of four over the past 50 years: 1969 to 2019. All figures are adjusted for inflation. For an average Canadian household, debt levels today are about six times higher than in 1970. Granted, we’re richer than we were in the 1970s, but six times richer? More important, are we richer as a nation? In 1970 the eastern oceans were full of cod and western regions were brimming with oil.

There are many ways to evaluate debt—to put it into perspective. Often it’s expressed as a percentage of GDP or of household income. The idea being that if the economy is bigger or incomes are larger, it’s okay to owe more. I want to argue that this is the wrong approach. I want to suggest a different and more concerning interpretation of ever-rising Canadian debt levels.

Debt rises when our financial outflows exceed inflows. If we need to pay out more than we are bringing in, we can borrow, and debt goes up. But implicit in this idea is another one: the day will come when inflows exceed outflows and we’ll have surplus money we can use to pay off the debt.

So let’s look at the graph in that light. Here’s what the graph shows: collectively, we Canadians couldn’t quite pay all our personal and government bills in the 1970s, so we borrowed money and debt increased. The same in the 1980s: we didn’t have enough so we borrowed and debt increased. This continued through the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. In each decade of the past half-century we couldn’t quite afford our lifestyles and infrastructure projects and social programs and day-to-day bills so we borrowed more money than we repaid, so debt rose—continuously, consistently.

So here’s the question that puts this debt into perspective: if we didn’t have enough money in any of the recent decades why are we confident that the situation will change in the future? Why, after five decades of increasing debt, are we confident that in the 2020s or 2030s or 2040s we can reverse the pattern of two generations and amass money so fast that we’ll not only be able to pay all our personal and government bills but we’ll also have large surpluses we can use to retire the debt we accumulated over 50 years? …a debt that now stands at about $400,000 per family of four.

Let’s explore that argument again, over a shorter time frame. Over just the past 15 years—2004 to 2019—the average Canadian household has increased its debt by about 45 percent—by about $110,000. But the recent decade-and-a-half were good years in much of Canada—unemployment was relatively low, the economy was usually strong, rising stock markets helped stoke investments and retirement accounts. In many parts of Canada most of the 2004-2019 period was a “boom” time. The economy was booming, yet we borrowed. Are we confident that our future will be even more … boomy? Because it’s in that future that we’re not only going to have to find ways to pay all the day-to-day bills in our households and legislatures, but also find large surpluses to retire debt. Are we confident that in the 2020s or 2030s our nation and our collective households will be so much richer than we were in the 2004-2019 period that that we’ll be able to retire all that debt?

My aim is certainly not to scold. Rising debt should not be seen as a personal problem, but rather as a collective error. Rather, my aim is to warn—to disabuse governments and my fellow citizens of a dangerous and possibly prosperity-curdling idea: that current debt levels are somehow safe and sustainable and that we should be calm as we or our governments pile on trillions more (as the trendlines in the graph suggest we will). Most of us have debts. But debt is a public policy issue, not a personal failing. Moreover, even those who do not have debt should not be smug. If, as a nation, our collective borrowing rises too far there will be a reckoning, and all will suffer as a result.

Every household must make its own decisions regarding mortgages and education spending and financing cars. But there is also a larger, collective, public-policy decision needed. Government leadership is needed to begin moving debt levels lower.