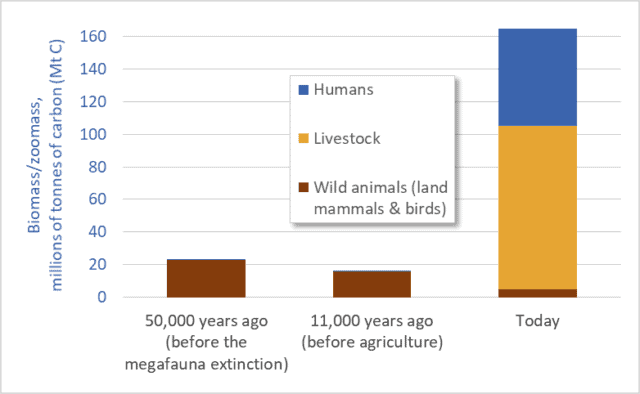

Humans and our livestock now make up 97 percent of all animals on land. Wild animals (mammals and birds) have been reduced to a mere remnant: just 3 percent. This is based on mass. Humans and our domesticated animals outweigh all terrestrial wild mammals and birds 32-to-1.

To clarify, if we add up the weights of all the people, cows, sheep, pigs, horses, dogs, chickens, turkeys, etc., that total is 32 times greater than the weight of all the wild terrestrial mammals and birds: all the elephants, mice, kangaroos, lions, raccoons, bats, bears, deer, wolves, moose, chickadees, herons, eagles, etc. A specific example is illuminating: the biomass of chickens is more than double the total mass of all other birds combined.

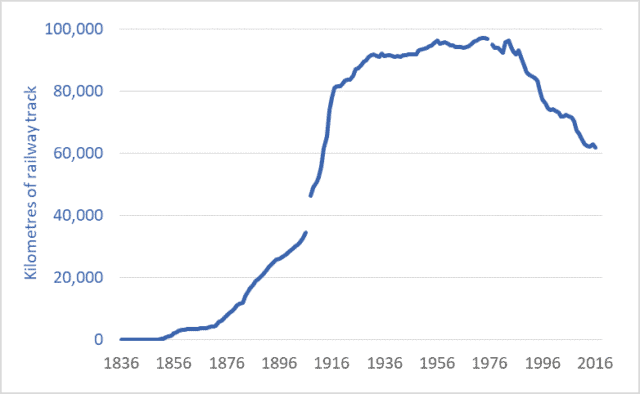

Before the advent of agriculture and human civilizations, however, the opposite was the case: wild animals and birds dominated, and their numbers and mass were several times greater than their numbers and mass today. Before the advent of agriculture, about 11,000 years ago, humans made up just a tiny fraction of animal biomass, and domesticated livestock did not exist. The current situation—the domination of the Earth by humans and our food animals—is a relatively recent development.

The preceding observations are based on a May 2018 report by Yinon Bar-On, Rob Phillips, and Ron Milo published in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Bar-On and his coauthors use a variety of sources to construct a “census of the biomass of Earth”; they estimate the mass of all the plants, animals, insects, bacteria, and other living things on our planet.

The graph above is based on data from that report (supplemented with estimates based on work by Vaclav Smil). The graph shows the mass of humans, our domesticated livestock, and “wild animals”: terrestrial mammals and birds. The units are millions of tonnes of carbon.* Three time periods are listed. The first, 50,000 years ago, is the time before the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction. The Megafauna Extinction was a period when Homo sapiens radiated outward into Eurasia, Australia, and the Americas and contributed to the extinction of about half the planet’s large animal species (>44 kgs). (Climate change also played a role in that extinction.) In the middle of the graph we see the period around 11,000 years ago—before humans began practicing agriculture. At the right-hand side we see the situation today. Note how the first two periods are dominated by wild animals. The mass of humans in those periods is so small that the blue bar representing human biomass is not even visible in the graph.**

This graph highlights three points:

1. wild animal numbers and biomass have been catastrophically reduced, especially over the past 11,000 years;

2. human numbers and livestock numbers have skyrocketed, to unnatural, abnormal levels; and

3. The downward trendline for wild animals visible in this graph is gravely concerning; this graph suggests accelerating extinctions.

Indeed, we are today well into the fastest extinction event in the past 65 million years. According to the 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment “the rate of known extinctions of species in the past century is roughly 50–500 times greater than the extinction rate calculated from the fossil record….”

The extinction rate that humans are now causing has not been seen since the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65 million years ago—the asteroid-impact-triggered extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs. Unless we reduce the scale and impacts of human societies and economies, and unless we more equitably share the Earth with wild species, we will enter fully a major global extinction event—only the sixth in 500 million years. To the other species of the Earth, and to the fossil record, human impacts increasingly resemble an asteroid impact.

In addition to the rapid decline in the mass and number of wild animals it is also worth contemplating the converse: the huge increase in human and livestock biomass. Above, I called this increase “unnatural,” and I did so advisedly. The mass of humans and our food animals is now 7 times larger than the mass of animals on Earth 11,000 or 50,000 years ago—7 times larger than what is normal or natural. For millions of years the Earth sustained a certain range of animal biomass; in recent millennia humans have multiplied that mass roughly sevenfold.

How? Fossil fuels. Via fertilizers, petro-chemical pesticides, and other inputs we are pushing hundreds of millions of tonnes of fossil fuels into our food system, and thereby pushing out billions of tonnes of additional food and livestock feed. We are turning fossil fuel Calories from the ground into food Calories on our plates and in livestock feed-troughs. For example, huge amounts of fossil-fuel energy go into growing the corn and soybeans that are the feedstocks for the tens-of-billions of livestock animals that populate the planet.

Dr. Anthony Barnosky has studied human-induced extinctions and the growing dominance of humans and their livestock. In a 2008 journal article he writes that “as soon as we began to augment the global energy budget, megafauna biomass skyrocketed, such that we are orders of magnitude above the normal baseline today.” According to Barnosky “the normal biomass baseline was exceeded only after the Industrial Revolution” and this indicates that “the current abnormally high level of megafauna biomass is sustained solely by fossil fuels.”

Only a limited number of animals can be fed from leaves and grass energized by current sunshine. But by tapping a vast reservoir of fossil sunshine we’ve multiplied the number of animals that can be fed. We and our livestock are petroleum products.

There is no simple list of solutions to mega-problems like accelerating extinctions, fossil-fuel over-dependence, and human and livestock overpopulation. But certain common sense solutions seem to present themselves. I’ll suggest just one: we need to eat less meat and fewer dairy products and we need to reduce the mass and number of livestock on Earth. Who can look at the graph above and come to any other conclusion? We need not eliminate meat or dairy products (grazing animals are integral parts of many ecosystems) but we certainly need to cut the number of livestock animals by half or more. Most importantly, we must not try to proliferate the Big Mac model of meat consumption to 8 or 9 or 10 billion people. The graph above suggests a stark choice: cut the number of livestock animals, or preside over the demise of most of the Earth’s wild species.

* Using carbon content allows us to compare the mass of plants, animals, bacteria, viruses, etc. Very roughly, humans and other animals are about half to two-thirds water. The remaining “dry mass” is about 50 percent carbon. Thus, to convert from tonnes of carbon to dry mass, a good approximation is to multiply by 2.

** There is significant uncertainty regarding animal biomass in the present, and much more so in the past. Thus, the biomass values for wild animals in the graph must be considered as representing a range of possible values. That said, the overall picture revealed in the graph is not subject to any uncertainty. The overall conclusions are robust: the mass of humans and our livestock today is several times larger than wild animal biomass today or in the past; and wild animal biomass today is a fraction of its pre-agricultural value.

Graph sources:

– Yinon M. Bar-On, Rob Phillips, and Ron Milo, “The Biomass Distribution on Earth,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 17, 2018.

– Anthony Barnosky, “Megafauna Biomass Tradeoff as a Driver of Quaternary and Future Extinctions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (August 2008).

– Vaclav Smil, Harvesting the Biosphere: What We Have Taken from Nature (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).