Want to understand your society and economy and the fate of petro-industrial civilization? If so, don’t “follow the money.” The stock market casino, quantitative easing, derivatives and other “financial innovations,” and the trillions of e-dollars that flit through the global monetary system each day obscure the real economy—the production and destruction of actual wealth: mining, farming, processing, transport, manufacturing, consumption, disposal. To understand where we are and where we may be going, we must follow more tangible flows—things that are real. We must follow the oil, coal, steel, concrete, grain, copper, fertilizers, salt, gravel, and other materials.

Our cars, homes, phones, foods, fuels, clothes, and all the other products we consume or aspire to are made out of stuff—out of materials, out of wood, iron, cotton, etc. And our economies consume enormous quantities of those materials—tens-of-billions of tonnes per year.

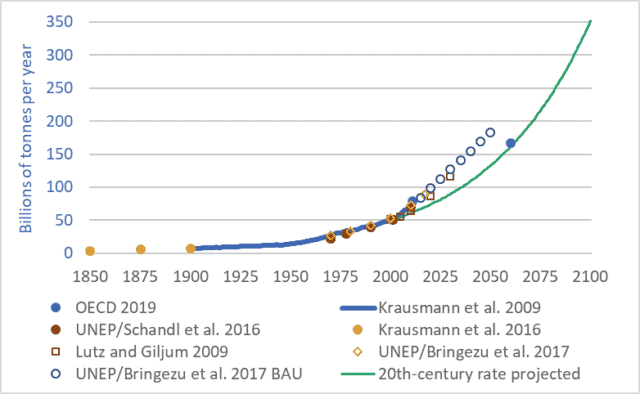

The graph above shows 250 years of actual and projected material flows through our global economy. The graph may initially appear complicated, because it brings together seven different sources and datasets and includes a projection to the year 2100. But the details of the graph aren’t important. What is important is the overall shape: the ever-steepening upward trendline—the exponential growth.

In 1900, global material flows totalled approximately 7 billion tonnes. The technical term for these material flows is “utilized materials”—the stuff we dig out of mines, pump up from oil or natural gas wells, cut down in forests, grow on farms, catch from the sea, dig out of quarries, and otherwise appropriate for human uses. These tonnages do not include water, nor do they include unused overburden, but they do include mine tailings, though this last category adds just a few percent to the total.

Between 1900 and 2000, global material tonnage increased sevenfold—to approximately 49 billion tonnes (Krausman et al. 2009). Tonnage rose to approx. 70 billion tonnes by 2010 (UNEP/Schandl 2016), and to approx. 90 billion tonnes by 2018 (UNEP/Bringezu 2018). At the heart of our petro-industrial consumerist civilization is a network of globe-spanning conveyors that, each second, extract and propel nearly 3,000 tonnes of materials from Earth’s surface and subsurface to factories, cities, shops, and homes, and eventually on to landfills, rivers and oceans, and the atmosphere. At a rate of a quarter-billion tonnes per day we’re turning the Earth and biosphere into cities, homes, products, indulgences, and fleeting satisfactions; and emissions, by-products, toxins, and garbage.

And these extraction, consumption, and disposal rates are projected to continue rising—to double every 30 to 40 years (Lutz and Giljum 2009). Just as we increased material use sevenfold during the 20th century we’re on track to multiply it sevenfold during the 21st. If we maintain the “normal” economic growth rates of the 20th century through the 21st we will almost certainly increase the volume and mass of our extraction, production, and disposal sevenfold by 2100.

But 2100 is a long way away. Anything could happen by then. Granted. So let’s leave aside the long-term and look only at the coming decade. Material throughput now totals about 90 billion tonnes per year, and is projected to rise to about 120 billion tonnes per year over the coming decade. For ease of math, let’s say that the average over the coming decade will be 100 billion tonnes per year. That means that between 2019 and 2029 we will extract from within the Earth and from the biosphere one trillion tonnes of materials: coal, oil, wood, fish, nickel, aluminum, chromium, uranium, etc. …one trillion tonnes. And we’ll send most of that trillion tonnes on into disposal in the ground, air, or water—into landfills, skyfills, and seafills. In the coming decade, when you hear ever-more-frequent reports of the oceans filling with plastic and the atmosphere filling with carbon, think of that trillion tonnes.

Postscript: “dematerialization”

At conferences and in the media there’s a lot of talk of “dematerialization,” and its cousin “decarbonization.” The idea is this: creating a dollar of economic activity used to require X units of energy or materials, but now, in countries such as Canada and the United States, creating a dollar of economic activity requires only two-thirds-X units. Pundits and officials would have us believe that, because efficiency is increasing and less material and energy are needed per dollar, the economy is being “dematerialized.” They attempt to show that the economy can grow and grow but we need not use more materials or energy. Instead of consuming heavy steel cars, we will consume apps, massages, and manicures. But this argument is wrong. Global material and energy use increased manyfold during the 20th century. The increases continue. A business-as-usual scenario will see energy and materials use double every 30 to 40 years. And just because the sizes of our economies, measured in abstract currencies, are growing faster, this does not change the fact that our use of energy and materials is growing. “Dematerialization” has no useful meaning in a global economy in which we are using 90 billion tonnes of materials per year and projecting the use of 180 billion tonnes by 2050. Our rate of extraction and consumption of materials is rising; the fact that the volume of dollar flows is rising faster is merely a distraction.

Sources for material flow tonnage:

Fridolin Krausmann et al., “Growth in Global Materials Use, GDP, and Population During the 20th Century,” Ecological Economics 68, no. 10 (2009).

Christian Lutz and Stefan Giljum, “Global Resource Use in a Business-as-Usual World: Updated Results from the GINFORS Model,” in Sustainable Growth and Resource Productivity: Economic and Global Policy Issues, ed. Bleischwitz et al. (Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing, 2009).

Stefan Giljum et al., Sustainable Europe Research Institute (SERI), “Resource Efficiency for Sustainable Growth: Global Trends and European Policy Scenarios,” background paper, delivered Sept. 10, 2009, in Manila, Philippines.

Julia Steinberger et al., “Global Patterns of Materials Use: A Socioeconomic and Geophysical Analysis,” Ecological Economics 69, no. 5 (2010).

UN Environmental Programme (UNEP) and H. Schandl et al., Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity: An Assessment Study of the UNEP International Resource Panel (Paris: UNEP, 2016).

Krausmann et al., “Long-term Trends in Global Material and Energy Use,” in Social Ecology: Society-Nature Relations across Time and Space, ed. Haberl et al. (Switzerland: Springer, 2016).

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), International Resource Panel, and Stefan Bringezu et al., Assessing Global Resource Use: A Systems Approach to Resource Efficiency and Pollution Reduction (Nairobi: UNEP, 2017).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019)