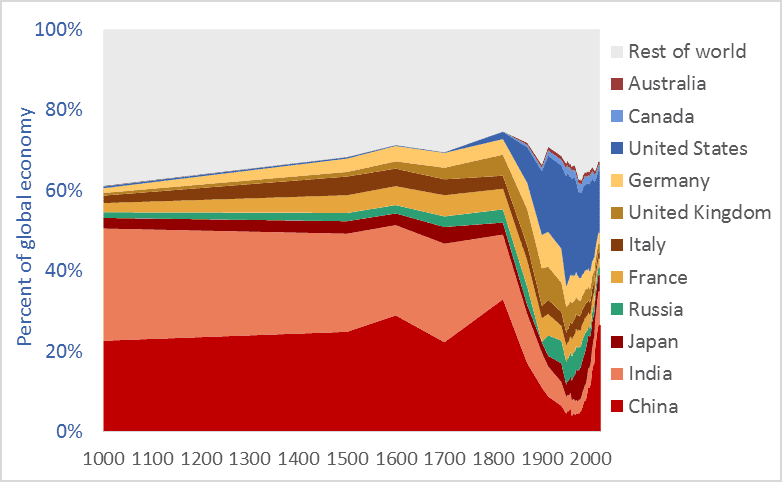

Some concepts stay with you your whole life and shape the way you see the world. For me, one such concept is complexity. Thinking about the increasing complexity of our human-made systems gives a window into future energy needs, the rise and fall of economies, the structures of cities, and possibly even the fate of our global mega-civilization.

In 1988, Joseph Tainter wrote a groundbreaking book on complexity and civilizations: The Collapse of Complex Societies. The book is a detailed historical and anthropological examination of the Roman, Mayan, Chacoan, and other civilizations. As a whole, the book can be challenging. But most of the important big-picture concepts are contained in chapters 4 and 6.

Regarding complexity, energy, and collapse, Tainter argues that:

1. Human societies are problem-solving entities;

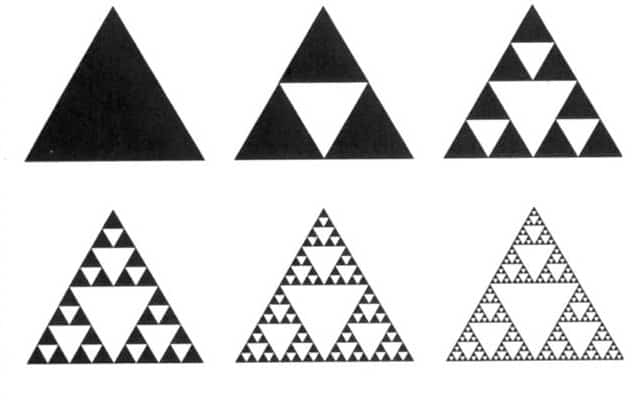

2. Problem solving creates complexity: new hierarchies and control structures; increased reporting and information processing; more managers, accountants, and consultants;

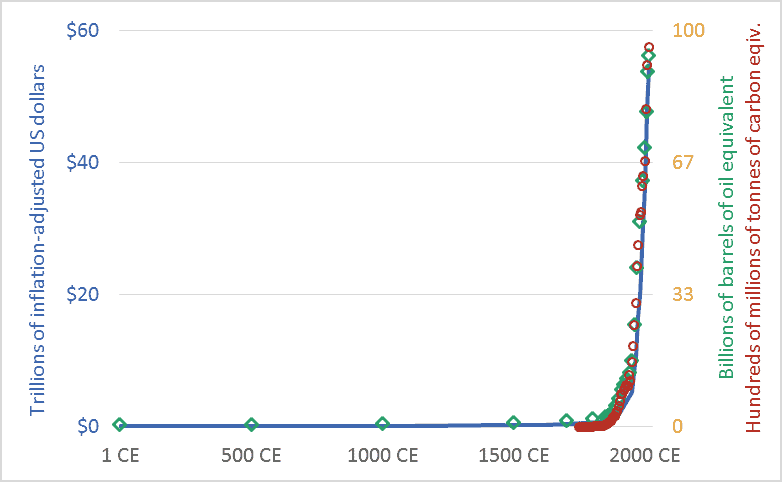

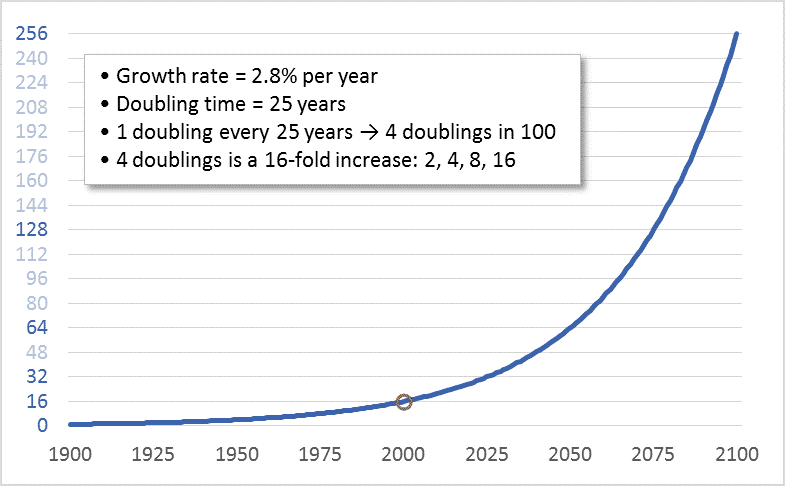

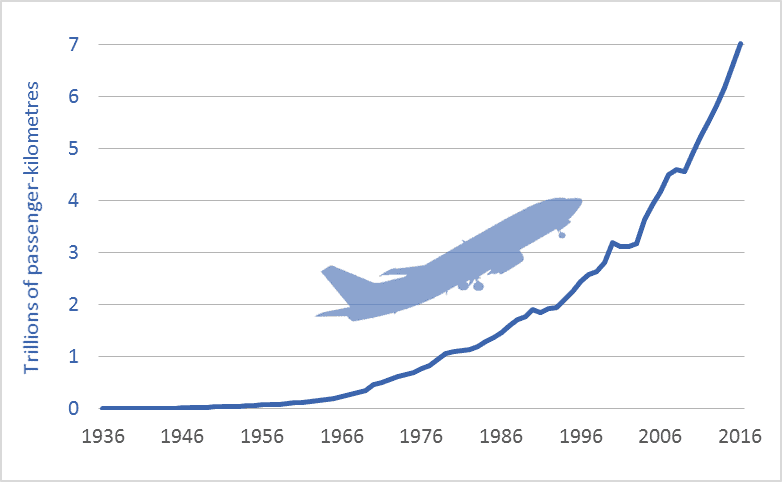

3. All human systems require energy, and increased complexity must be supported by increased energy use;

4. Investment in problem-solving complexity reaches a point of declining marginal returns: (energy) costs rise faster than (social or economic) benefits; and

5. Complexity rises to a point where available energy supplies become inadequate to support it and, in that state, an otherwise withstandable shock can cause a society to collapse. For example, the western Roman Empire, unable to access enough bullion, grain, and other resources to support the complexity of its cities, armies, and far-flung holdings, succumbed to a series of otherwise unremarkable attacks by barbarians.

Societies certainly are problem-solving entities. Our communities and nations encounter problems: external enemies, environmental threats, resource availability, disease, crime. For these problems we create solutions: standing armies and advanced weaponry, environmental protection agencies, transnational energy and mining corporations, healthcare companies, police forces.

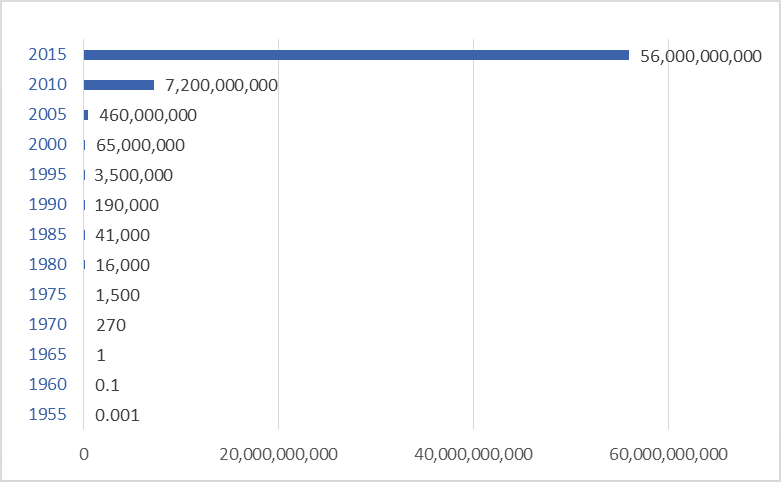

Problem-solving, however, entails costs in the form of complexity. To solve problems we create ever-larger bureaucracies, new financial products, larger data processing networks, and a vast range of regulations, institutions, interconnections, structures, programs, products, and technologies. We often solve problems by creating new managerial or bureaucratic roles (e.g., ombudsmen, human resources managers, or cyber-security specialist); creating new institutions (the UN or EU); or developing new technologies (smartphones, smart bombs, geoengineering, in vitro fertilization). We accept or even demand this added complexity because we believe that there are benefits to solving problems. And there certainly are, at least if we evaluate benefits on a case-by-case basis. Taken as whole, however, the unrelenting accretion of complexity weighs on the system, bogs it down, increases energy requirements, and, as Tainter argues, eventually outstrips available energy supplies and sets the stage for collapse. We should keep this in mind as we push to further increase the complexity of our civilization even as energy availability may be contracting. Tainter is telling us that complexity has costs—costs that civilizations sometimes cannot bear. This warning should ring in our ears as we consider the internet of things, smart-grids, globe-circling production chains, and satellite-controlled autonomous cars. The costs of complexity must be paid in the currency of energy.

Complexity remains a powerful concept for understanding our civilization and its future even if we don’t share Tainter’s conclusion that increasing complexity sets the stage for collapse. Because embedded in Tainter’s theory is an indisputable idea: greater complexity must be supported by larger energy inflows. Because of their complexity, there simply cannot be low-energy versions of London, Japan, the EU, or the global trading system. As economies grow and consumer choices proliferate and as we increase the complexity of societies here and around the world we necessarily increase energy requirements.

It is no longer possible to understand the world by watching money flows. There are simply too many trillions of notional dollars, euros, and yen flitting through the global economy. These torrents of e-money obscure what is really happening. If we want to understand our civilization and its future, we must think about energy and material flows—about the physical structure and organization of our societies. Complexity is a powerful analytical concept that enables us to do this.