“People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!” So spake Greta Thunberg at the United Nations on September 23rd, 2019.

Thunberg, a sixteen-year-old without a university education, has had the insight, clarity, and courage to say what ten-billion-dollars worth of Ph.D. economists haven’t: that continued economic growth is, at best, unsustainable and probably much worse: a malignant illusion driving us to destroy our biosphere, civilization, and future. The project of making the current global economy four or eight times larger is a suicide pact.

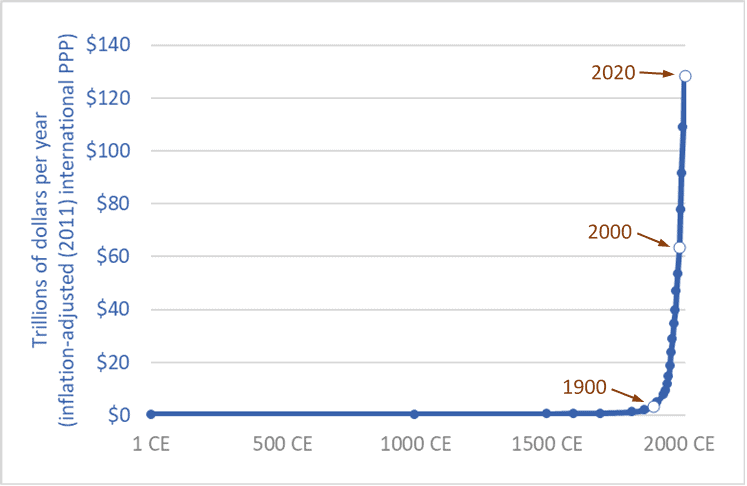

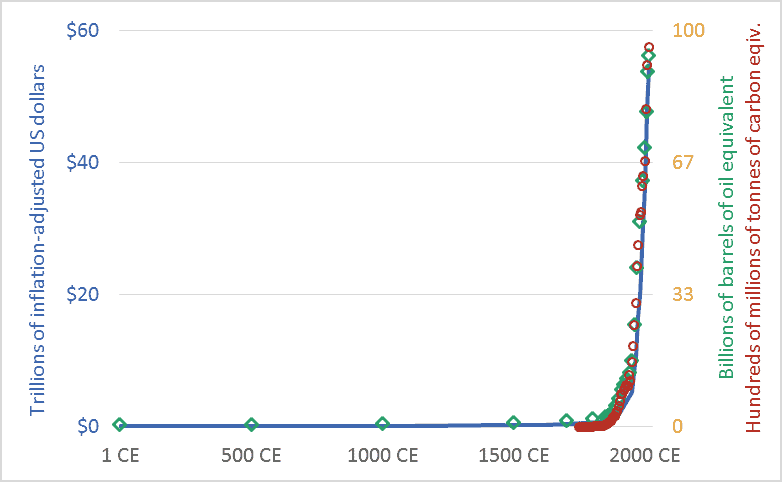

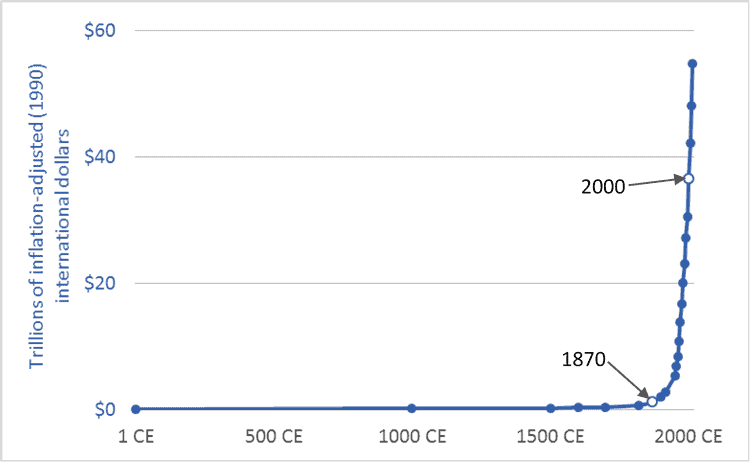

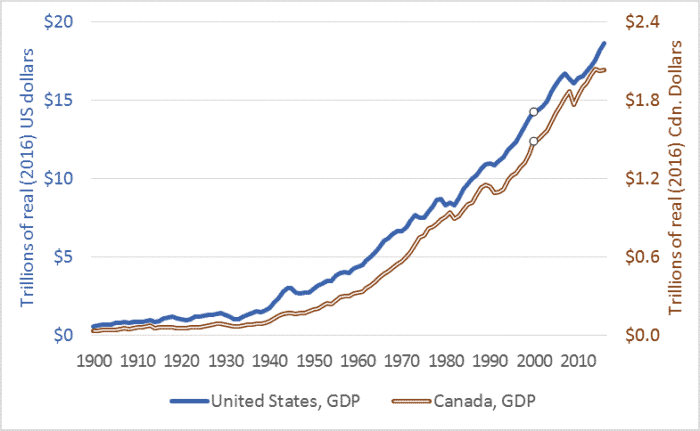

The graph above places our 21st century economy in its long-term context. It shows the size of the global economy (Gross World Product) from 1 CE to 2020. The units are trillions of US/international dollars adjusted for inflation (constant 2011 dollars). The main source is the World Bank, with historical data from Angus Maddison. (Pre-20th century values are, by necessity, estimates by Maddison.)

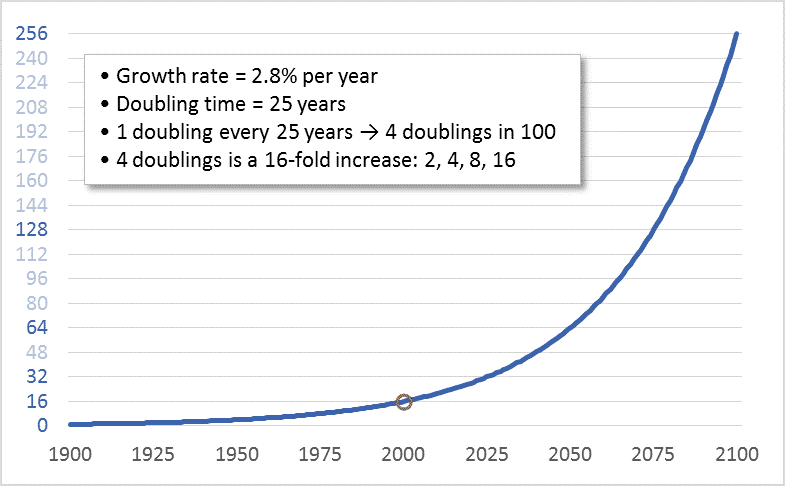

The years 1900, 2000, and 2020 are highlighted. Sometime in 2020 the size of the global economy will surpass 127 trillion dollars. When it does, it will be twice as large as it was in 2000. The economy will have doubled in size in just 20 years. This shouldn’t be a surprise. Sustained growth rates of 3.5 percent leads to a doubling every 20 years. (Recall the Rule of 70.)

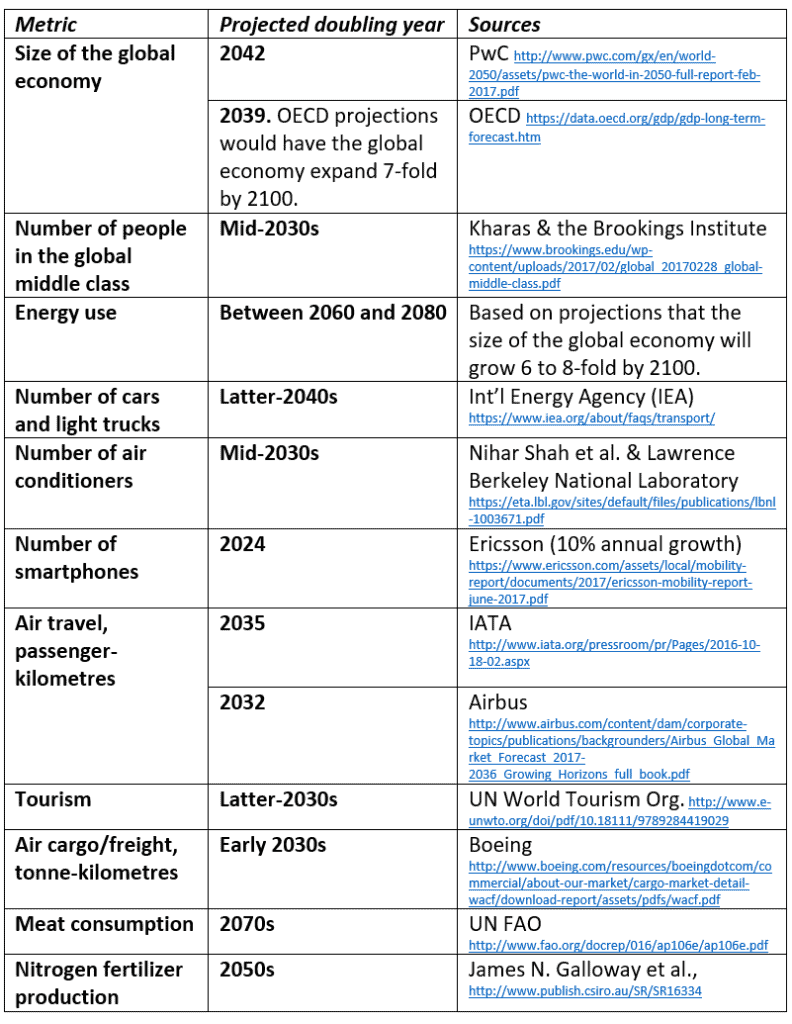

Going forward, if we maintain current rates of growth—three to four percent annually—the economy will be twice as large again by 2040 or soon after—making it four times larger than in 2000. Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, land, and biosphere will be hosting four 2000-sized economies.

And by 2060 or 2070, another doubling will bring the global economy to eight times its 2000 level. And there’ll still be more than enough time left in this century to double it again—at least a 16-fold increase in size in a single century, if we stay the course. If we accomplish this, we will be reprising the 18-fold increase seen during the 20th century.

Of course, we won’t do this—we won’t make the global economy 8 or 16 times larger. Within a generation or two nearly everyone on the planet will be living in a post-growth economy: either because we’ve had the wisdom to end runaway exponential growth and put the biosphere first, or because we have not.

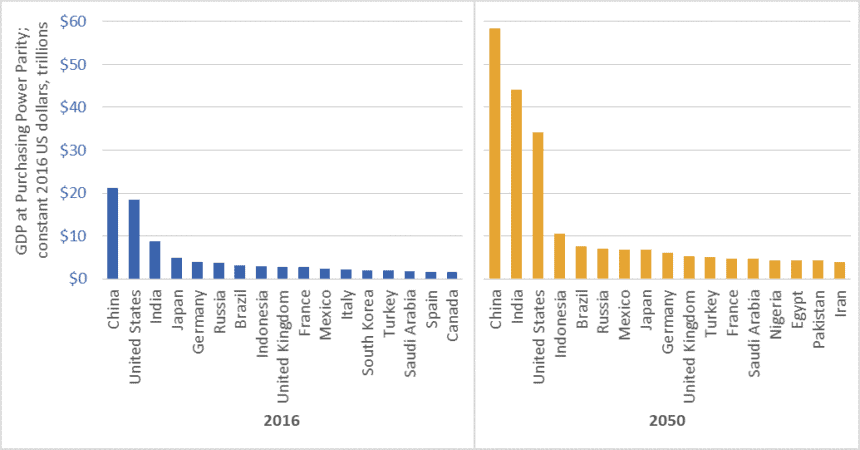

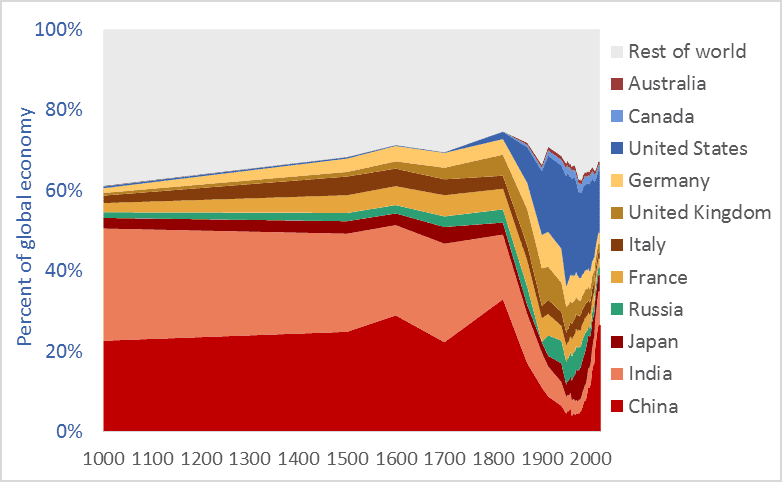

The end of growth, inescapable in the medium term, will bring numerous problems, such as how will we deal with the equity claims of the poor if we can no longer rely on the convenient fictions of “a rising tide raises all boats” and “anyone (everyone?) can grow up to be rich.” While the end of growth must come for nearly all within a few decades, it must come first for those of us who are richest, so that growth can continue in places where people are poorer. Those of us who enjoy jet vacations need to step off the growth escalator first so that growth can continue for others and deliver to them running water and refrigerators. The end of growth casts into sharp relief a series of moral problems.

But the end of growth will also solve many problems. We will be forced to take less of our economy’s productivity and bounty in the form of consumer products and more in the form of free time and low-emission leisure—more time with family, more time with friends drinking coffee or wine, more time with culture and nature; more discussion, poetry, romance, literature, and contemplation. Most of the people in the fast-expanding (-metasticizing?) global middle class are living high-stress, low-quality, time-impoverished lives. Stepping off the growth escalator can be part of a larger civilizational, cultural, and spiritual shift in which we rediscover meaning and purpose beyond getting and spending.

Thunberg is neither sage nor prophet. And one need be neither to see what is absolutely, inescapably obvious: growth must and will soon end. But we have a choice: We can deny the fact of growth’s imminent end and continue in the fairy tale and massively deplete and damage the planet in a last frenzied attempt to squeeze out one or two more doublings, or we can be as mature as a sixteen-year-old, admit the obvious, get on with the needed changes, and reap the benefits of slower, saner, more sustainable, more enjoyable lives.

Sources for graph:

– World Bank, Databank website: “GDP, PPP (constant 2011 international $)”

– Angus Maddison, The World Economy, Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective (Paris: OECD, 2001); Angus Maddison, Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007)