How can we reduce agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by half by mid-century? And how can steps to do so help strengthen and safeguard family farms? These two questions are the focus of a new report written by Darrin Qualman in collaboration with the National Farmers Union (NFU). The report is entitled Tackling the Farm Crisis and the Climate Crisis: A Transformative Strategy for Canadian Farms and Food Systems and it’s available from the NFU website.

The report looks at the climate crisis and the farm income crisis. It concludes that our farms’ high emissions and low net incomes have the same cause: overdependence on purchased inputs: fertilizers, chemicals, fuels, etc.

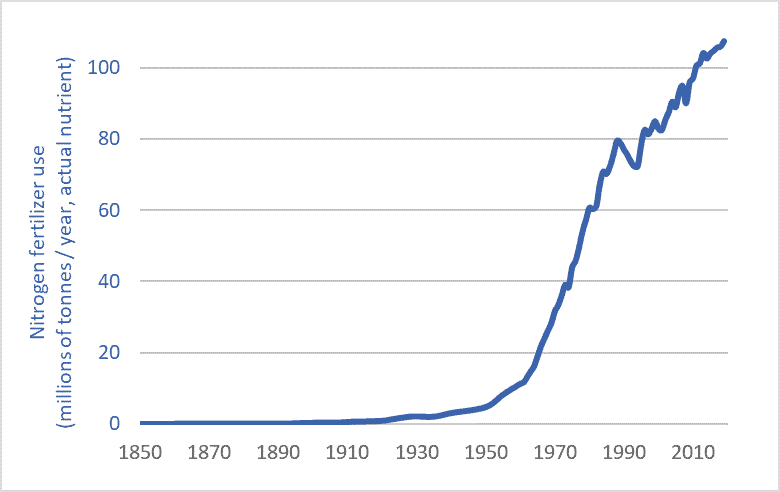

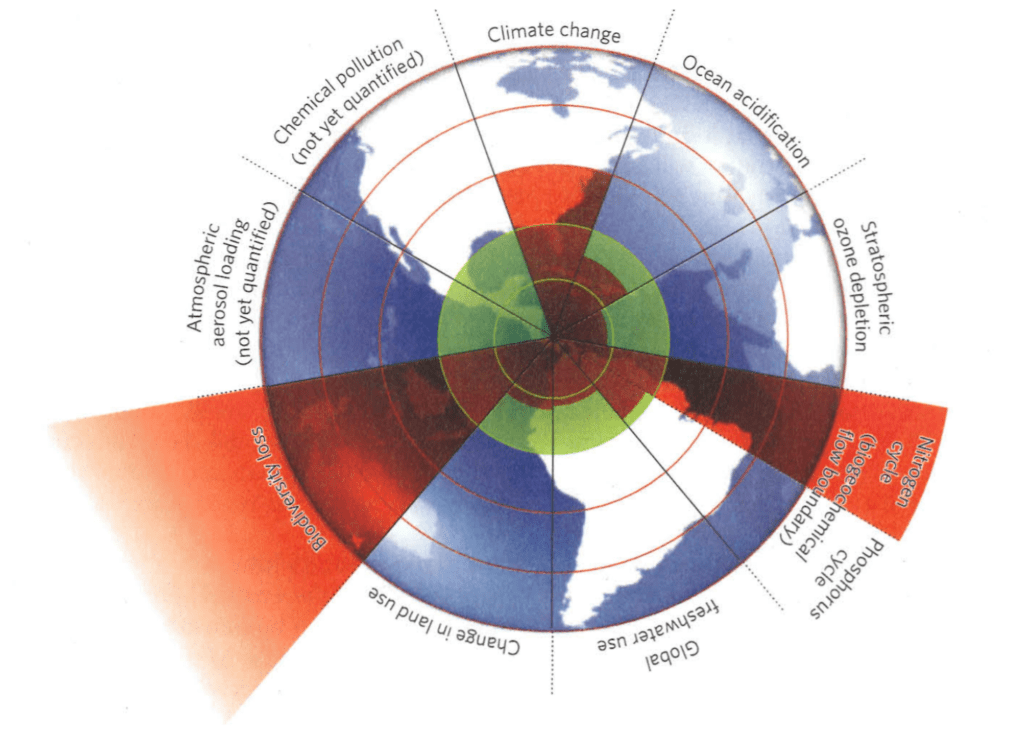

The report shows clearly that the GHG emissions coming out of our farm and food systems are simply the downstream byproducts of the petro-industrial inputs we push in. “Push in millions of gallons of fossil fuels and they will come out as millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide. Push in megatonnes of fertilizers and they will come out as megatonnes of nitrous oxide. As we have doubled and redoubled input use, we have doubled and redoubled the GHG emissions from agriculture,” states the report. From this novel observation comes an inescapable conclusion: “Any low-emission food system will be a low-input food system.”

The report takes a long-term view and states that “10,000 years of human history makes one thing crystal clear: farming does not create GHG emissions; petro-industrial farm inputs create GHG emissions.” It goes on to state that “Two things happen when farmers become overdependent on purchased inputs: emissions go up, and net incomes go down.”

The report is optimistic, however, arguing that solutions to climate problems can also be solutions to farm income problems. On average, farmers are now retaining just five cents out of every dollar they earn. The other 95 cents go to pay for inputs—to pay fertilizer, chemical, seed, fuel, and machinery companies and other input and service providers. But as input use is reduced as a way to reduce emissions, margins and net incomes can go up. Steps to deal with the climate crisis can also be steps to solve the farm income crisis.

The report explores dozens of practical on-farm measures and government policies that can, taken together, reduce agricultural emissions by half by mid-century. The report, however, does not underestimate the scale of the task ahead. It acknowledges that “farmers, other citizens, all sectors, and all levels of government must mobilize, with near-wartime-levels of commitment and effectiveness, to slash emissions. ”

The report is a hopeful blueprint for the transformation of our farms and food systems. “We are looking at a future wherein agriculture must increasingly re-merge with nature and culture to create a much more integrated, life-sustaining, and community-sustaining agroecological model of human food provision, nutrition, and health.”

Darrin Qualman worked as Director of Research for the National Farmers Union from 1996 to 2010. He is the author of the book, published in 2019, Civilization Critical: Energy, Food, Nature, and the Future.

Click HERE to read the report.