Check out this brilliant ‘long-form comic’ by Stuart McMillen: Energy Slaves. Click here or on the URL above.

Many Canadians and Americans struggle financially. Millions are unemployed. Many others live paycheque-to-paycheque. A 2017 report by the US Federal Reserve Board found that 40 percent of US citizens couldn’t cover an unexpected expense of $400 without selling something or borrowing money. There’s a lot of denial and misunderstanding regarding the financial challenges faced by a large portion of our fellow citizens.

Equally, though, there is misunderstanding, denial, and myth-making regarding those among us who are more financially secure, those who are well off—“the rich.” Most glaring is the way we mischaracterize the sources of our wealth, luxury, and ease. We lie to ourselves and each other regarding why we have it so good. The rich often claim that their wealth is a result of “hard work.” We hear people objecting to even the smallest tax increase, saying: “I worked hard for my money and no one is going to take it from me.”

The reality, however, is quite the opposite. The rich don’t work very hard. Every poor women or girl in Asia or Africa who gets up at dawn to walk many kilometres to carry home water or firewood for her family works harder than the world’s multi-millionaires and billionaires. Every farmer with a hoe or toiling behind an oxen works harder than any CEO. My farmer grandparents worked far harder than I do, yet I live much better. I would be self-delusional in the extreme to attribute my middle-class luxury to “hard work.”

No, those of us in North America, the European Union, and elsewhere in the world who enjoy privileged lives live well, not because we work hard, but because of the vast energy windfall of which we are the beneficiaries. We live lives of comfort and ease because our work is done for us by “energy slaves.”

A human worker can toil at a constant rate of about one-tenth horsepower. Working hard all year at that rate I can do about 200 horsepower-hours worth of work—hoeing or hauling or digging. But if I add up the work accomplished by non-human energy—by fossil fuels and machines and by electricity from various sources and electric motors—I find that, on a per-capita average, that quantity is 100 times my annual work output. For every unit of work I do, the motors and machines that surround me do 100 units. Those of us who live comfortable, high-consumption lives are subsidized 100-to-1 by work we do not do. And the richest among us enjoy the largest of those subsidies.

Let me state that another way: If I look around me, at the hurtling cars and trucks, the massive quantities of cloth and steel and concrete created each year, the rapidly expanding cities, the roads that get paved and the bridges built, I am seeing a quantity of building and digging and hauling and making that is 100 times greater than the humans around me could accomplish. Human muscles and energies provide one percent of the work needed to create and maintain our towering, hyper-productive, petro-industrial civilization; but electricity, fossil fuels, other energy sources, engines, and machines provide the other 99 percent. We and our human bodies put in 1 unit of work, but enjoy the benefits of 100. That is the reason so many of us live better than the kings, sultans, and emperors of previous centuries.

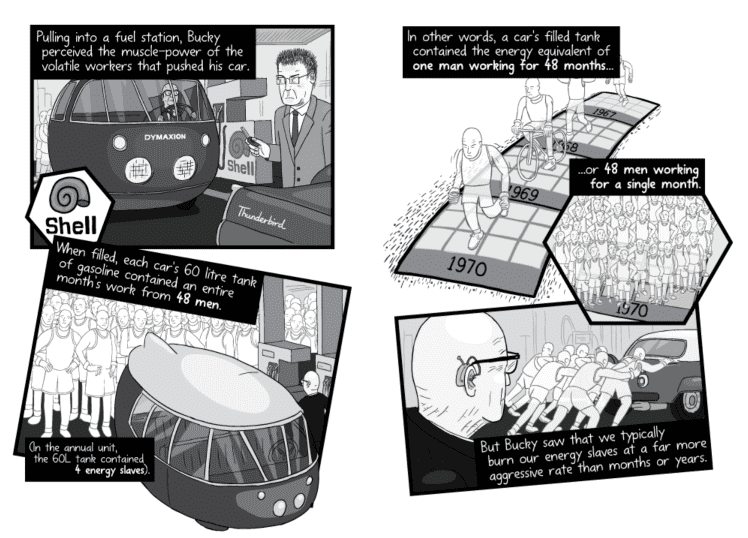

As Stuart McMillen brilliantly illustrates in his long-form comic, Energy Slaves, it is as if each of us has a whole troupe of slaves toiling for our benefit. It is the work of these virtual assistants that propel us along, create our homes and cities, raise our food, pump our water, and make our goods.

We will face many hard questions as we progress through the twenty-first century: can we continue to consume energy at the rates we do now? How can we generate that energy without fouling the atmosphere and destabilizing the climate? How do we more equitably share access to energy among our soon-to-be 11-billion-person population? How do we address energy poverty? And all these questions and issues are tied to others, such as to issues of income inequality. But a vital first step is to begin to talk honestly about the real sources of our wealth, to acknowledge that we enjoy undeserved subsidies, to admit that we are all (energy) lottery winners, and to approach the future with attitudes of humility and gratitude rather than entitlement. We cannot navigate the future if we cling to the self-serving and self-aggrandizing myths of the past.

Comments are closed.