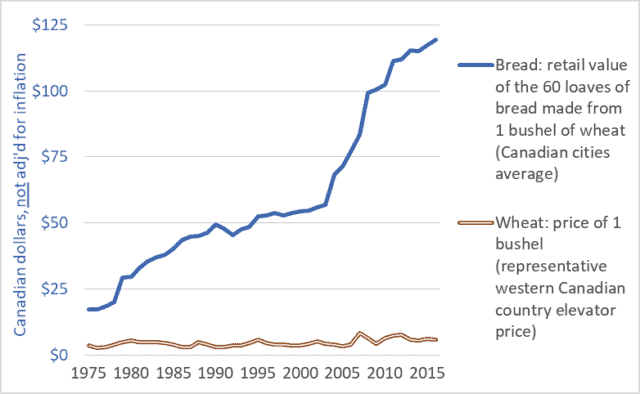

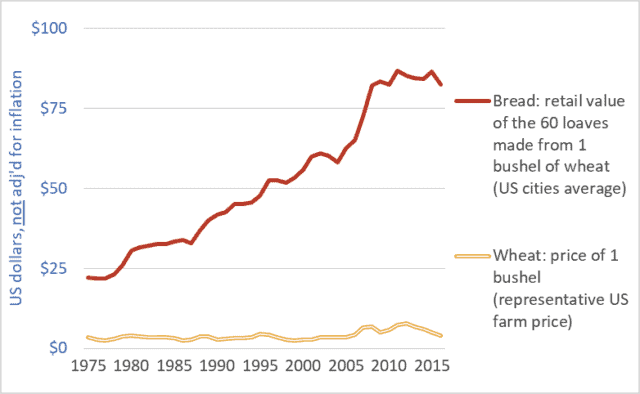

United States retail store bread price and farm-gate wheat price, 1975-2016

It’s been said before but it bears repeating: farmers are making too little because others are taking too much. For instance, food retailers, processors, grain companies, and railways are taking far too large a share of the retail price of bread. And the share taken by these companies is increasing—choking off the flow of dollars to our family farms. At the same time, these same corporations are profiteering by driving up the prices of the staple foods we all need to feed ourselves and our families.

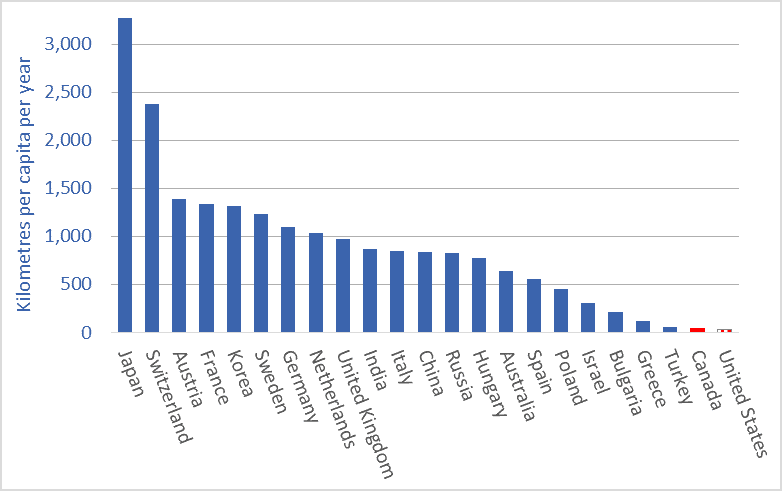

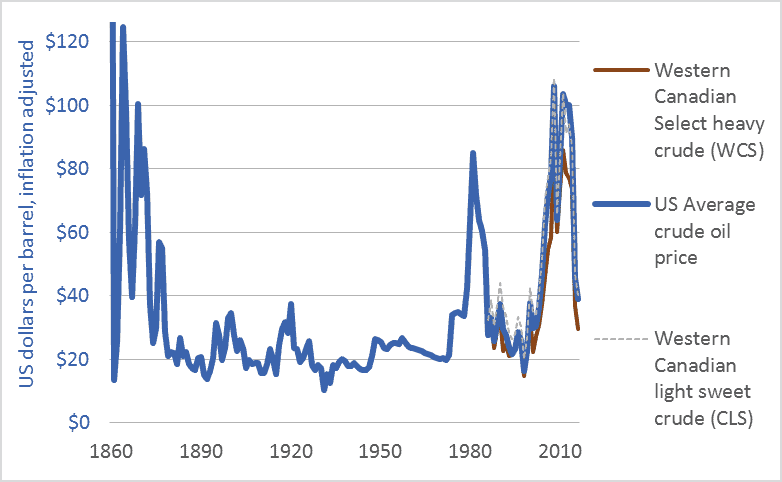

This week’s two graph show data for the US and Canada. Both graphs show the price of a bushel of wheat (the relatively flat line across the bottom of each graph) and the retail value of the approximately 60 loaves of bread that can be produced from a bushel of wheat (the upward-trending line in each graph). The wheat prices are farm-gate or country elevator values. The units are Canadian or US dollars, as appropriate, not adjusted for inflation.

The units are not important, however. What is important is the widening gap between what consumers pay for bread and the amount of money that makes it back to the farm. This growing gap represents the ever-larger share taken by food retailers, flour millers and other processors, railways, and elevator companies and grain traders.

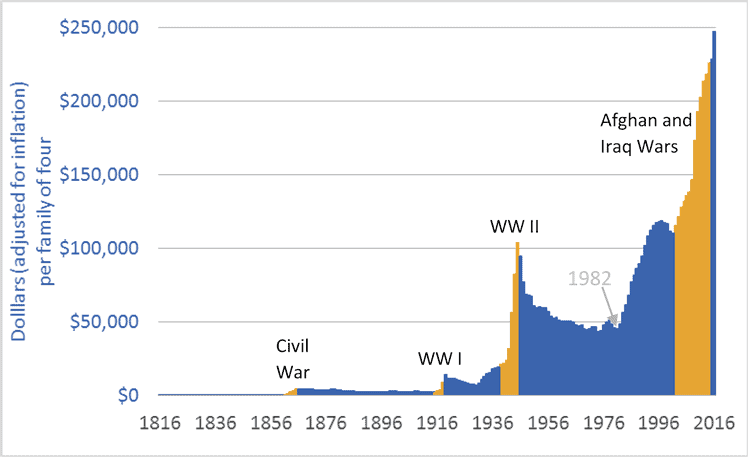

Very little of the money spent in grocery stores makes it back to American or Canadian farms. Compounding this problem is the fact that most of the money that does make it back to these farms is quickly captured by powerful farm-input companies. (See details here.) Corporations upstream and downstream from farmers use their market power to capture huge profits for themselves while reducing net farm income to zero in many years. To keep farms solvent, governments and citizens must step in with taxpayer-funded farm support payments. In Canada, these payments have totaled $100 billion dollars over the past three decades, and more than $400 billion in the US. From some perspectives, the primary beneficiaries of these payments are the executives and shareholders of the dominant agribusiness/food corporations.

Finally, there is the issue of efficiency. Farmers are relentlessly urged to become more efficient. Indeed, they are forced to increase efficiency simply to remain solvent in the face of declining farm-gate prices and rising input costs. Farmers are so efficient today that they can produce grains and other products for 1970s’ prices. But what of efficiency elsewhere in the system? What does it indicate about the efficiency of huge corporate flour millers and food retailers if they must constantly take more and more money for themselves? Are they becoming less efficient as they get larger? Or are they simply using their increasing size and power to capture more profit for themselves? And if citizens are going to be made to pay more for food anyway, then why badger farmers to become ever more efficient?

Farmers are the primary victims of the abuses of power within the food system. But everyone is hurt as we are made to pay increased taxes to fund farm-support programs and to pay increased retail prices to support the outsized profit needs of the dominant food-system transnationals and their shareholders.

Graph sources:

Canadian bread: Statistics Canada, Consumer Prices and Price Indexes (Catalog number 62-010); CANSIM Table 326-0012.

US bread: Bureau of Labour Statistics, “Bread prices 1980-2015“.

Canadian wheat: Government of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan Agriculture and Agri-food, “StatFacts-Canadian Wheat Board Payments for No. 1 CWRS”; CANSIM Table 002-0043.

US Wheat: United States Department of Agriculture, “Wheat Yearbook”