Fractal collapse is an important, useful idea. It helps us understand that a society, economy, political system, or civilization may not “fall,” but rather become pock-marked and weakened—shot through with micro-collapses.

The United States may be in an advanced state of collapse. There are many indicators that this is the case. The national debt, nearly $20 trillion, about a quarter-million dollars per family of four (see my “US national debt per family”), seems unrepayable. America’s former industrial heartland is now mostly rustbelt, and parts of Detroit look like sets for “Walking Dead” or “The Road.” Climate change is bearing down from one side and resource depletion from another. Its democratic system—rotted by dark money, voter suppression, gerrymandering, the distortions of the Electoral College, and messianic populist politics—has delivered gridlock, ideologues, cartoon-level analyses of complex issues, and, now, Trump. Many of the manufacturing jobs that have not moved to Asia may soon be taken by robots. Inequality and incarceration-rates are at record highs. One could extend this list to fill pages.

Despite the preceding, I’m not predicting that America (or Greece or Australia or England) will “fall”—pitch into rapid and irreversible economic contraction and social disintegration. Instead, fractal collapse is more likely. In fractal collapse, parts of a system fail, at various scales, but the system, in diminished form, carries on. We’re seeing this in America. We see the collapse of a household here (perhaps a result of the opioid crisis), and a neighbourhood, there; a city declines rapidly (think Detroit or Scranton) and a county declares bankruptcy. Collapse occurs in various places and at various scales but the aggregate entity moves forward. And such collapses are not predictable—they do not just happen to poor people or in the “poor” places. Suddenly and unexpectedly, the investment banks collapse, then General Motors becomes insolvent. The Senate and House of Representatives cease to function properly. Collapse is not a single event. As we are seeing it play out now—amid the hyper-energized and dominant “industrial” economies—collapse is multiple, iterative, and repeated across scales: it is fractal.

And collapse is not monolithic or pervasive. Indeed, some parts of the system expand and prosper. The US is manufacturing billionaires at a record pace, the stock market continues to climb, output of everything from corn to natural gas is up, and Google and Apple are world-leading corporations. A hallmark of collapse is that societies become dis-integrated, allowing some parts to fall as other parts rise.

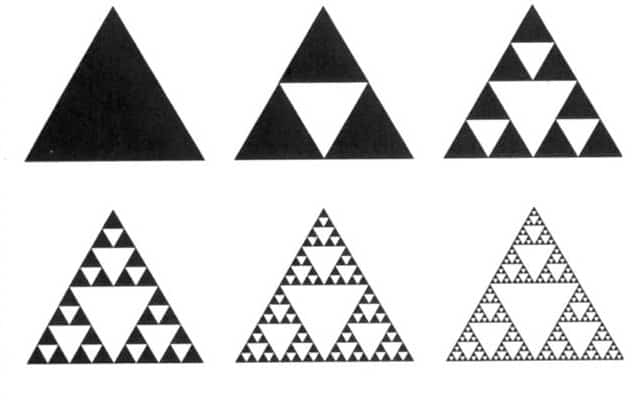

The image above is a Sierpinski triangle or “gasket.” It helps visualize this idea of fractal collapse. Step by step, the original triangle shape develops more holes and loses area, but it does not disappear. its outlines remain apparent.

To make a Sierpinski gasket, we start with an equilateral triangle. Then we identify the mid-points of each side and use these as the vertices of a new triangle, which we remove from the original. (See the top-middle triangle, above.) This leaves us with three equilateral triangles. We repeat this process over and over; we iterate. From each remaining triangle we remove the middle, leaving three smaller triangles. The Sierpinski gasket and its repeated holing can serve as a visual metaphor for the fractal collapse that may now be hollowing out many of the world’s nations.

The future is not binary, not rise or fall. Increasingly, nations may become less homogeneous. Some parts may expand and prosper while other parts may wither or fail. The overall trendline may not be upward, however, but rather downward. Our future may not be a train wreck, but rather a slow dilapidation. Not with a bang but a wimper. We can change this outcome. But currently very few are trying.

The intellectual history of the idea of fractal collapse is not wholly clear. The concept came out of the physical sciences and has been popularized as a description of social and economic collapse by author and analyst John Michael Greer.