New reports in highly-respected journals Science and Nature (links here and here) tell us that the world’s economies and societies need to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions to zero before mid-century. This has huge implications for the ways in which we power our cities, homes, food systems, transportation networks, and manufacturing plants. Our civilization must undergo a rapid energy-system transformation, similar in magnitude and effects to previous energy transitions, such as the replacement of wood by fossil fuels in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Enormous changes are on the way.

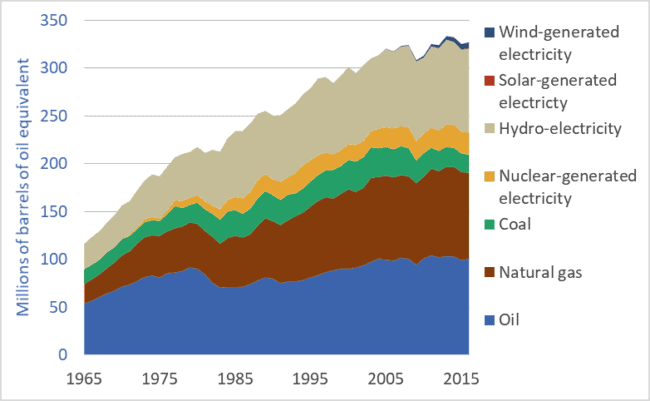

To understand our possible futures it is useful to know something of the past. The graph above shows Canadian primary energy consumption from 1965 to 2016. The units are “millions of barrels of oil equivalent”—that is, all energy sources have been quantified based on their energy content relative to the energy contained in a barrel of oil. (“Primary energy” is energy in the form in which it is first produced: oil from a well, coal from a mine, hydroelectricity from a dam, or photovoltaic electricity from a solar panel. Much of the coal and some of the natural gas listed in the graph above is turned into electricity in power generating stations.)

This multi-decade look at Canadian energy use reveals both good and bad news. Most obvious, it shows that Canada has nearly tripled its overall energy consumption since 1965. Today, on a per-capita basis, Canadians consume more energy than citizens of most other nations. Our very high per-capita energy use will make our energy transition more difficult and costly.

On the positive side, our rate of increase in energy use is slowing—the top line of the graph is flattening out. Partly, this indicates that Canadians are using energy more wisely and efficiently. But another factor may be the transfer of heavy industry and manufacturing to other nations; Canadian energy use may be growing more slowly because more of our industrial and consumer goods are made overseas. Also, the graph may not include the full extent of energy consumed in international shipping and aviation. If Canada’s full share of global water and air transport were added, our energy use may appear higher still.

The graph has some good news in that fossil fuel use in Canada is declining. Coal, oil, and natural gas provide less energy to our economy today than they did 20 years ago. Coal use, especially, has been cut. On the negative side, any downward trendline in fossil fuel use is not nearly steep enough to intersect zero by 2050.

Good news is that Canada already has a large number of low-emission energy sources in place. We are the world’s third-largest producer of hydro-electricity. We also produce significant amounts of electricity from nuclear powerplants. Starting in the 1980s and continuing today, Canada has produced about a third of its primary energy from low-emission sources: including nuclear, hydro, wind, and solar electricity generation.

This brings us to perhaps the most important fact revealed by the graph: the very slow rate of installation of new low-emission energy sources—especially solar and wind. Today, solar and wind provide just 2 percent of our primary energy. Indeed, the contribution of solar power is barely visible in the graph.

An energy transformation is critical. Global greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2020 and ramp down sharply, reaching zero three decades later. This will be, by far, the most rapid energy transition in human history. Canadian action so far falls far short of the scale and rate required.

P.S. A new book on the history of Canadian energy systems has recently been published. Powering up Canada: A History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600 contains chapters on the energy sources for the fur trade, early horse-powered agriculture, the rise in the importance of coal in Canada, and chapter on the development of the oil and gas sectors.

Graph sources: BP Statistical Review of World Energy.