There’s a lot being written about China’s rapid push to install solar panels and wind turbines (e.g., see here). And as the US withdraws from the Paris Agreement, pundits have suggested that this opens the door for Chinese leadership on renewable energy and climate change mitigation (see here). And China certainly has taken over global production of solar photovoltaic (PV) panels. But is this talk of China’s low-carbon, renewable-energy future premature and overoptimistic? Are we just pretending, because so little positive is happening where we live, that something good is happening somewhere? Chinese energy consumption data provides a corrective to the flood of uncritical news stories that imply that China will save us.

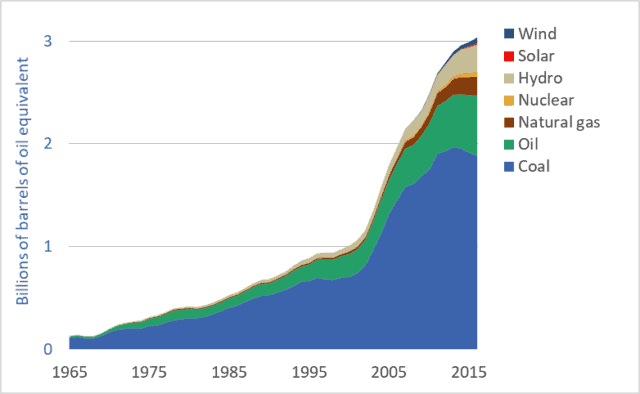

This week’s graph shows how various energy sources are being combined to power China’s rapidly growing and industrializing economy. The units are “billions of barrels of oil equivalent”: all energy sources have been recorded based on their energy content relative to the energy contained in a barrel of oil. Similar data for Canada can be found here. US data is coming soon.

Is the Chinese energy system being rapidly decarbonized? Is China powered by wind turbines? Or by coal? The data can support some optimism for the future, but at present, most of the news is bad. China remains the world’s largest consumer of fossil fuels and largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Let’s look at the good-news-bad-news story that is China’s energy system.

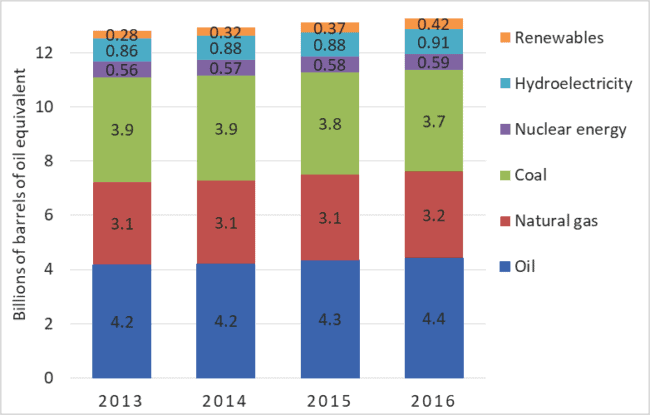

First, the good news: As is visible in the graph, China’s fossil fuel consumption has been flat-lined since 2013, and coal consumption is falling. Further, CO2 emissions have been declining since 2014. China has ceased, or at least paused, its rapid increase in its consumption of fossil fuels.

China is also leading the world in the installation of renewable energy systems, especially wind and solar generation systems (see here). Chinese wind power production and consumption is growing exponentially—doubling approximately every two years. Solar power production and consumption is growing even more rapidly and has increased 25-fold in just the past 5 years. China has also invested massively in hydro dams, which can produce electricity with far fewer GHG emissions than coal-fired power plants.

But it would be naive or premature to simple project Chinese solar and wind power growth rates into the future and conclude that the nation will soon slash its emissions. China’s coal-fired powerplants are relatively new and unlikely to be decommissioned prematurely. No matter how cheap solar panels become, installing new solar arrays will never be cheaper than simply continuing to produce electricity with already-built coal plants.

Moreover, the graph makes clear that the current contribution of solar and wind to China’s energy system is small—about 2 percent of total consumption. And while this portion will undoubtedly grow, there will be huge challenges for China as renewables make up a larger and larger percentage of its electricity generation capacity. With a less-than-state-of-the-art power grid, China will face difficulties dealing with the fluctuations and uncertainty created by intermittent power sources such as wind and solar power.

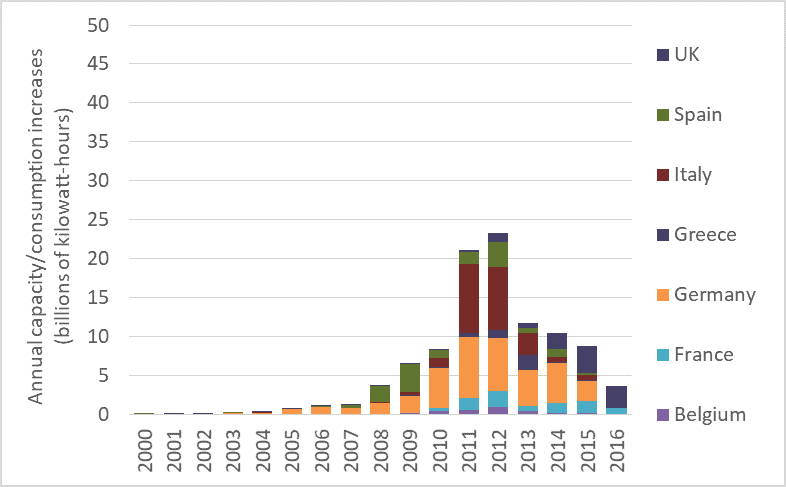

Is China the leader we’re looking for? If so, it is a very odd choice. China has doubled its fossil fuel use and emissions since 2003. It is the world’s largest fossil fuel consumer and GHG emitter, and these two facts will almost certainly remain true for decades to come. The idea that China will pick up the slack as American and European commitments to decarbonization falter is dangerous wishful thinking. Moreover, it should not be the case that we should expect China to lead. It was us—the UK, US, EU, Canada and similar early-adopters of fossil fuels, cars, and consumerism—that overfilled the atmosphere with GHGs over the past century. China has come late to the fossil fuel party. Asking it to lead the way out the door—asking it to take the lead in decarbonization—is as inappropriate as it is naive.

Here’s one last reason why it’s wrong to look for China to lead the way to a zero-carbon future: Per person, China’s emissions are about half of those in Canada and the US (source here). Is it right for those of us neck deep in high-emission consumerist car-culture to look to relatively poor people with relatively low emissions and urge them to “go first” down the road of carbon reduction?