The following draws upon extensive research by ETC Group. I have been privileged to serve on ETC’s Board of Directors for several years.

1. What is “geoengineering”? It is the intentional, largescale, technological manipulation of Earth’s systems. Geoengineering is usually discussed as a solution to climate change, but it could also be used to attempt to de-acidify oceans or fix ozone holes. Here, I’ll concentrate on climate geoengineering.

2. There are two main types of climate geoengineering:

i. Technologies to partially shade the sun in order to reduce warming (called “solar radiation management” or SRM). For example, high-altitude aircraft could be used to dump thousands of tonnes of sulphur compounds into the stratosphere to form a reflective parasol over the Earth.

ii. Attempts to pull carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the air. One proposal is ocean fertilization. In theory, we could dump nutrients into the ocean to spur plankton/algae growth. As the plankton multiply, they would take up atmospheric CO2 that has dissolved in the water. When they die, they would sift down through the water column, taking the carbon to the ocean floor.

3. The effects of geoengineering will be uneven and damaging. For example, sun-blocking SRM technologies might lower the global average temperature, but regional temperature changes would probably be uneven. Other geoengineering techniques—cloud whitening and weather modification—could similarly alter temperatures in some parts of the planet relative to others. And if we change relative regional temperatures we would also shift wind and rainfall patterns. Geoengineering will almost certainly cause droughts, storms, and floods. Going further, however, all droughts, storms, and floods (even those that might have occurred in the absence of geoengineering) could come to be seen as caused by geoengineering and the governments controlling those climate interventions. If we go down this path, there will no longer be any “acts of God”; weather will become a product of government.

4. These technologies are dangerous in other ways. Seeding the stratosphere with sulphur particles could catalyze ozone depletion. Shifts in rain and temperature patterns may cause shifts in ecosystems and wildlife habitats. Multiplying plankton biomass may affect fish species distribution and biodiversity. Moreover, as with any enormously powerful technology, it is simply impossible to foresee the full range of unintended consequences.

5. Geoengineering is unilateral, undemocratic, inequitable, and unjust. In a geoengineered world, who will control the global thermostat? Solar radiation management and similar schemes will inevitably be controlled by the dominant governments and corporations—a rich-nation “coalition of the dimming.” But benefits and costs will be distributed unequally, creating winners and losers. Where will less powerful nations appeal if they find themselves on the losing end? Our climate interventions will be calibrated to maximize benefits to rich nations: the same countries that have benefited most from fossil fuel combustion and that have caused the climate crisis. We appear to be contemplating a triple injustice: poor nations will be denied their fair share of the benefits of fossil fuel use; hit hardest by climate change; and left as collateral damage from geoengineering. Finally, geoengineering is undemocratic in another way. It is a choice to pursue technical interventions rather than social or political reforms. It reveals that many governments and elites would risk damaging the stratosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere rather than risk difficult conversations with voters, CEOs, or shareholders.

6. Geoengineering embodies and proliferates a certain worldview: masculine, nature-dominating, imperialistic, managerial and technocratic, hostile to limits, and hubristic.

7. Geoengineering will create conflicts. Because technologies such as SRM are transboundary and have the potential to shift weather patterns they can lead to charges that other nations are stealing rain and, ultimately, food. To get a sense of the potential for conflict, imagine the US reaction to unilateral deployment of weather- and climate-altering technologies by Russia or China.

8. It is untestable. Small-scale experiments with SRM or similar technologies will not reveal potential side-effects. These will only become evident after planet-scale deployment, and perhaps years after the fact, as weather systems move toward new equilibria.

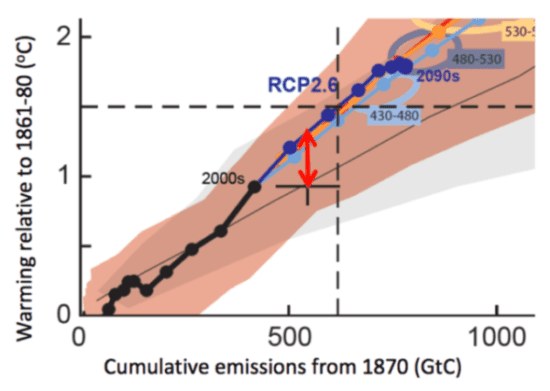

9. Deployment may be irreversible. Once we start we might not be able to stop. Geoengineering would probably proceed alongside continued greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. But if we deploy sun-blocking technologies and simultaneously push atmospheric CO2 levels past 500 or 600 parts per million, we wouldn’t be able to terminate our dimming programs, no matter how damaging the effects of long-term geoengineering are revealed to be. If we did stop, high GHG levels would trigger sudden and dramatic warming. We risk locking ourselves into untestable, unpredictable, uncontrollable, and planet-altering technologies.

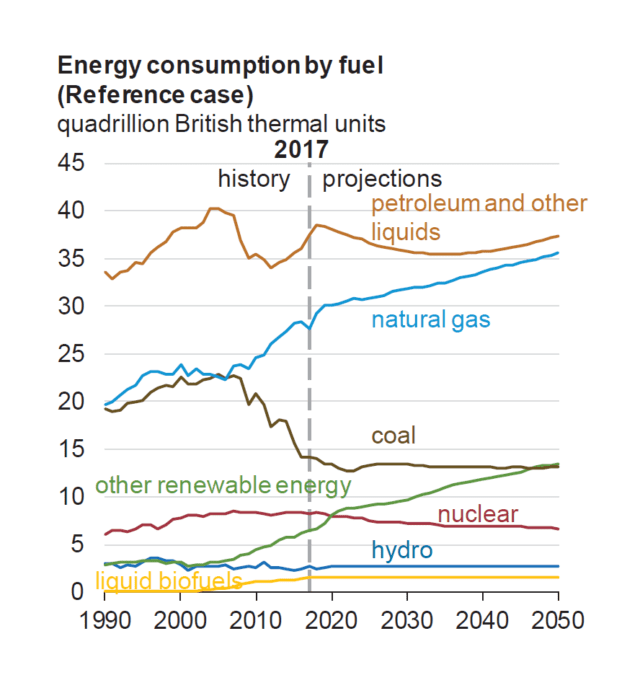

10. Can geoengineering “buy us time”? Proponents argue that these technologies can buy us some time: time humanity needs in order to ramp up emissions reductions. But geoengineering is more likely to buy time for the status quo, to prolong unsustainable fossil fuel production and energy inefficiency, and to blunt and delay urgent and effective action. The effect of geoengineering is not so much to buy time as to waste time.

11. There will be attempts to pressure us into accepting geoengineering. Geoengineering proponents may soon raise the alarm and claim that we must accept these risky technologies or face even worse damage from climate change. “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” they will say. From these same sources may come arguments that geoengineering is necessary to hold global average temperature increases below 1.5 or 2 degrees and thus spare the world’s poorest and most vulnerable peoples. Such arguments would be both ironic and duplicitous. The same government and corporate leaders who today deny or downplay climate change, or deny the need for rapid action to cut emissions, may tomorrow be the ones raising the alarm, and claiming that there is no solution other than geoengineering. They may pivot from claiming that there is no problem to claiming that there is no alternative.

12. Geoengineering will be pushed by the rich and powerful. A growing number of corporations, elites, and politicians see the solution to climate change, not in emissions reduction, but in massive techno-interventions into the atmosphere or oceans to block the sun or suck up carbon. When he was CEO of Exxon, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said of climate change: “It’s an engineering problem, and it has engineering solutions.” Exxon employs many geoengineering proponents and theorists. Former executive at oil company BP and former Under-Secretary for Science in the Obama administration Steven Koonin is lead author of a report entitled Climate Engineering Responses to Climate Emergencies. Virgin Airlines CEO Richard Branson offered a $25 million prize to anyone who could solve climate change by geoengineering. Bill Gates and other Microsoft billionaires are funding geoengineering research. Newt Gingrich is the former speaker of the US House of Representatives and a Vice Chairman of Donald Trump’s transition team. His views on geoengineering are worth quoting because they may be representative of a growing sentiment among political and corporate leaders. Gingrich wrote in a 2008 fundraising letter:

“[T]he idea behind geoengineering is to release fine particles in or above the stratosphere that would then block a small fraction of the sunlight and thus reduce atmospheric temperature.

… Instead of imposing an estimated $1 trillion cost on the economy …, geoengineering holds forth the promise of addressing global warming concerns for just a few billion dollars a year. Instead of penalizing ordinary Americans, we would have an option to address global warming by rewarding scientific innovation.

My colleagues at the American Enterprise Institute are taking a closer look at geoengineering, and we should too. …

Our message should be: Bring on the American Ingenuity. Stop the green pig.”

For reasons outlined above and many others, we must not go down the path of geoengineering. These technologies—massive government and corporate interventions into the core flows and structures of the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere—are among the most dangerous initiatives ever devised. Geoengineering must be banned; it is untestable, uncontrollable, unjust, probably irreversible, and potentially devastating. There exist better, safer options: rapid and dramatic emissions reductions; and a government-led mobilization toward a transformation of global energy, transport, industrial, and food systems.