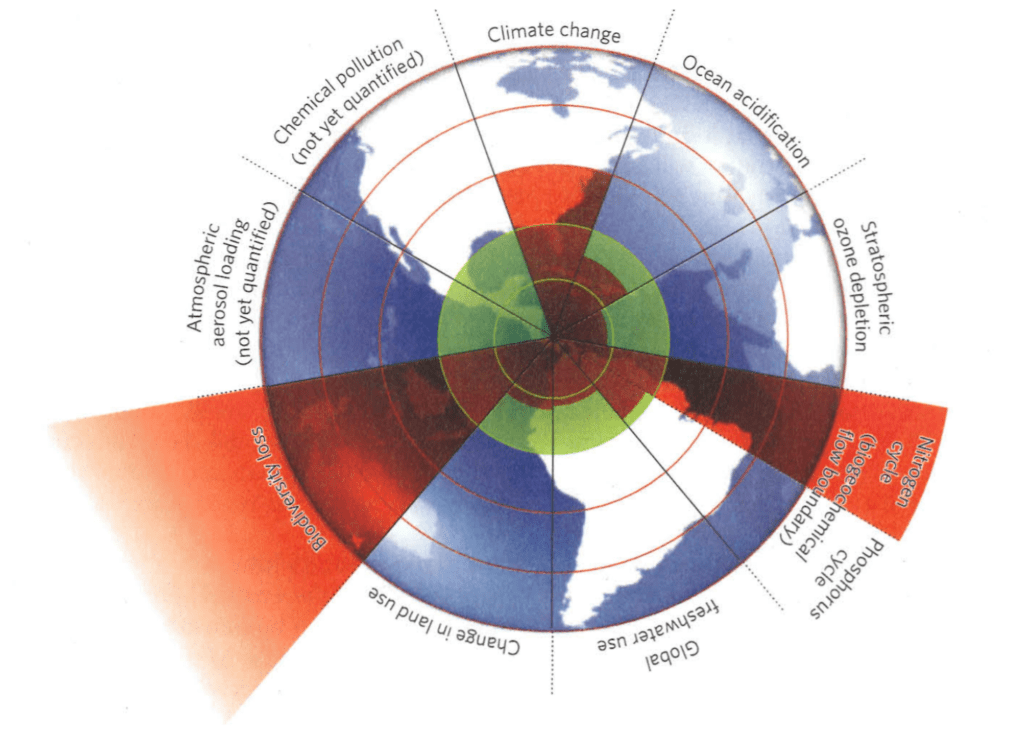

If there was no climate crisis we’d all be talking about the nitrogen crisis. Humans have super-saturated Earth’s biosphere with reactive nitrogen, setting off a cascade of impacts from species shifts, ecosystem changes, and extinctions to ocean dead zones and algae-clogged lakes. When scientists surveyed the many threats to the biosphere to determine a “safe operating space” for planet Earth, the areas in which they concluded that we’d pushed furthest past “planetary boundaries” were climate change, species extinction, and nitrogen flows. The graphic below, from the journal Nature, shows the extent to which we’ve transgressed safe planetary boundaries. Note nitrogen—the red wedge, lower right.

Source: Reproduced from: Johan Rockström, Will Steffen, et al., “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” Nature 461, no. 24 (2009).

A nitrogen primer

Nitrogen is indispensable for life—a building block of proteins and DNA. Nitrogen (N) is one of the most important plant nutrients and the most heavily applied agricultural fertilizer. Nitrogen is common in the atmosphere—making up 78 percent of the air we breath. But this atmospheric N is inert; non-reactive—it can’t be used by plants. In contrast, reactive, plant-usable N is just one-one-thousandth as abundant in the biosphere as nitrogen gas is in the atmosphere. For hundreds-of-millions of years, plants have struggled to find sufficient quantities of usable N.

But humans have intervened massively in the planet’s nitrogen cycles—effectively tripling the quantity of N flowing through terrestrial ecosystems—through farmland, forests, wetlands, and grasslands. In intensively cropped areas, nitrogen flows are now ten times higher than natural levels.

Here’s the most important part: nitrogen is a fossil-fuel product. Natural gas is the main input for making N fertilizer. That gas provides the tremendous energy, heat, and pressure needed to split atmospheric nitrogen molecules and combine N atoms with hydrogen to make reactive compounds. The amount of energy needed to create, transport, and apply one tonne of N fertilizer is nearly equal to two tonnes of gasoline. Nitrogen is one way that we push fossil-fuel energy into the food system in order to push more food out. We turn fossil fuels into fertilizer into food into us.

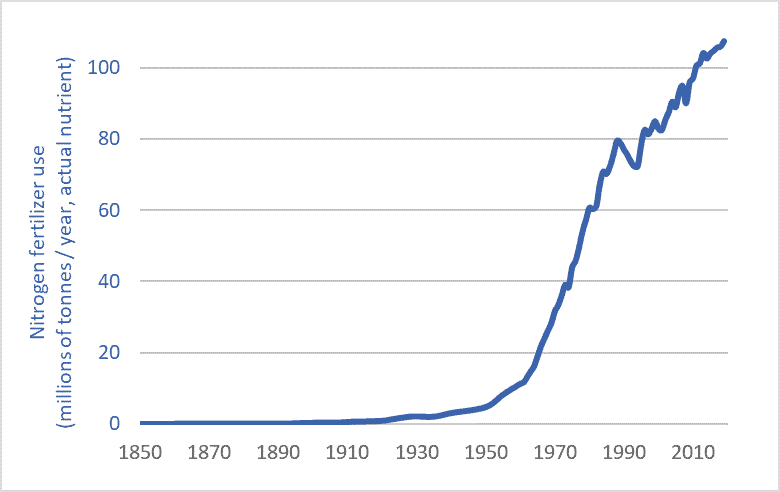

Humans managed to increase global food production about eight-fold during the 20th and early 21st centuries.* There’s more tonnage coming out of our food system. But that system is linear, so if there’s more food coming out one end, there must be more inputs being pushed into the other end—more energy, chemicals, and fertilizers. The graph above shows how humans have increased N fertilizer inputs three-hundred-fold since 1900 and thereby helped increase human food outputs eight-fold, and human populations four-and-a-half-fold. By pushing in a hundred million tonnes of fossil-fuel-derived fertilizer we can push out enough food to feed an additional six billion people. (for more information on nitrogen, see chapters 3 and 28 of my recent book, Civilization Critical.)

Greenhouse gas emission from nitrogen fertilizer

The nitrogen crisis is compounded by the fact that N production and use drive climate change. The production and use of nitrogen fertilizer is unique among human activities in that it produces large quantities of all three of the main greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide (from fertilizer-production facilities fueled by natural gas); nitrous oxide (from soils over-enriched by factory-made N); and methane (from the production and distribution of natural gas feedstocks and from the fertilizer-production process, i.e., from fracking, leaking gas pipelines, and from emissions from fertilizer plants). A 2019 science journal article reported that actual methane emissions from fertilizer plants may be 100 times higher than previously assumed. Emissions from N fertilizer production and use make up about half the total emissions from agriculture in many regions. It’s fertilizer, not diesel fuel, that’s the largest emissions source on many farms.

Alternatives

We cannot continue to push massive quantities of petro-industrial N fertilizer into our farm fields and ecosystems. Luckily there are alternatives and partial solutions. these include:

– Getting nitrogen from natural sources: legumes and better crop rotations;

– Scaling back our demand for agricultural products: reducing food waste; rethinking biofuels; minimizing nutritionally disfigured food (sugar pops and tater tots); ceasing the attempt to globally proliferate North American levels of meat consumption;

– Funding agronomic research into low-input, organic, and agro-ecological production systems; and

– Rationalizing and democratizing our food system—moving away from systems based on yield-, output-, trade-, and profit-maximization; corporate control; farmer elimination; and energy- and emission-maximization to new paradigms based on food sovereignty, health and nutrition-maximization, input-optimization, emissions-reduction, and long-term sustainability.

Any maximum-input, maximum-output agricultural system will be a high-emission system. Input reduction, however, can boost sustainability and net farm incomes while reducing energy use and emissions. Cutting N use is key.

* The FAO records a four-fold increase in grain production between 1950 and 2018 and it is likely that production roughly doubled between 1900 and 1950, so an eight- to ten-fold increase in production is likely between 1900 and 2018.

Graph sources:

– International Fertilizer Association (IFA);

– Vaclav Smil, Enriching the Earth (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001);

– UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), FAOSTAT; and

– Clark Gellings & Kelly Parmenter, “Energy Efficiency in Fertilizer Production and Use.”