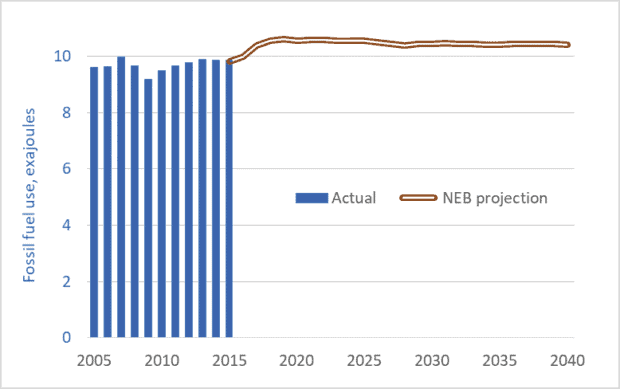

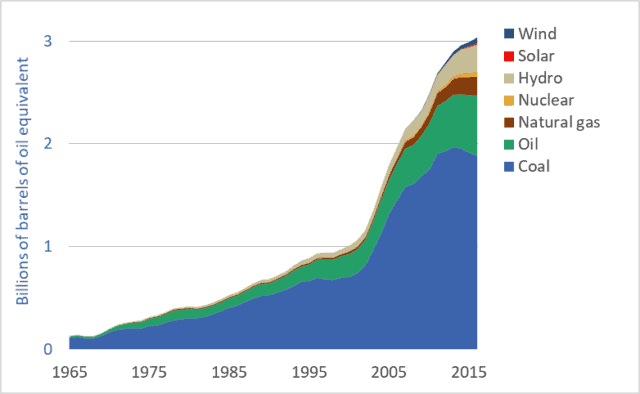

The graph above is based on data from a recent report by Canada’s National Energy Board (NEB)—a federal government agency. The October 26 report, Canada’s Energy Future 2017, predicts that Canadians will be consuming fossil fuels at the same rate in 2040 as we are today. The NEB is projecting that fossil fuel use will not fall, nor will attendant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The graph’s blue bars show Canadian fossil fuel use over the past 11 years. The brown line shows the NEB’s projections for the future. The units, exajoules, are not important. What is important is that the NEB predicts no drop in fuel consumption.

Most important, is that the NEB’s projections take into account the federal government’s carbon tax. Ottawa has announced that the provinces must impose a carbon tax of $10 per tonne in 2018, escalating to $50 per tonne by 2022. All provinces must impose a tax, or some equivalent carbon-pricing scheme.

At the Paris climate talks in 2015, Canada joined other nations in committing to limit the global average temperature increase to 2.0 degrees C (relative to pre-industrial levels). To help achieve that goal, Canada has made an international commitment to reduce its GHG emissions by 30 percent (relative to 2005 levels) by 2030. The NEB is, in effect, saying that Canada will fail to meet its commitment of a 30 percent reduction; the carbon tax, along with all other measures announced so far, will not cause a decline in fossil fuel use or emissions.

The preceding should surprise no one. The federal government’s carbon tax starts out at $10 per tonne of carbon—equivalent to about 2¢ per litre of gasoline. Over the next half-decade, it rises to $50 per tonne—about 11¢ per litre. Many Canadians do not know the price of gasoline to the nearest dime. And gasoline prices over the past year were down as much as 40¢ compared to three years ago. An 11¢ per litre carbon tax is not going to cause gasoline consumption to fall. Similarly modest taxes on other fuels will likewise prove ineffective.

Canadians need to understand that they are being deceived. Politicians—eager for re-election and afraid of hard conversations with voters—are understating the magnitude of the climate crisis and overestimating the effectiveness of our actions to counter the threat.

How do we actually reduce fossil fuel use, cut emissions, and stabilize the climate? A carbon tax is needed, but it must be much higher: $200 to $300 per tonne—equivalent to 50¢ to 75¢ per litre of gasoline. But such a tax is unbearable for citizens (and politicians) unless 100 percent of the total tax collected is rebated back to citizens on a per-capita basis. We need a carbon-tax-and-refund system. Under such a system, we would all pay taxes on gasoline, home heating fuel, etc. and pay indirectly on the energy embedded in our products. Goods that required a lot of energy to produce or transport would cost more. But offsetting these new costs, we would receive back all the carbon tax money collected, on a per-capita basis. Thus, if a person’s energy consumption is below average, he or she would finish the year money ahead—his or her per-capita refund would exceed the carbon taxes paid. On the other hand, someone who wants to drive a Hummer and heat and cool a huge home will come out money behind. Another way of thinking about this tax-and-refund system is that it transfers money to those doing the right things from those doing the wrong things. And the former group can take their carbon tax refunds and invest them in home energy retrofits, solar panels, and other emission-reduction measures, setting the stage for even larger carbon tax savings next year.

The NEB is telling us we’re not on track. But we can change course. Bold and rapid policy action now can reduce emissions by 30 percent and help limit temperature increases to 2 degrees. But we must act.

Graph source: National Energy Board